Tuesday

11 MAY 2021

7:45 pm – 9:45 pm Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsDebussy in Resonance

Joanna Goodale piano-gongs-bols

YouTube-crowdfunding concert on 13 March Live concert (30min) by the Franco-Swiss pianist Joanna Goodale on YouTube. She will present her 2nd album in homage to Debussy, financed in part by a WeMakeIt crowdfunding The recording will take place at the Salle de musique in La Chaux-de-Fonds, in collaboration with RTS and My Big Geneva, with the support of the Tempo Foundation and our faithful partners.« La musique est un art libre, un art jaillissant, un art de plein air, un art à la mesure des éléments, du vent, du ciel et de la mer! »

Claude Debussy, 1901 Debussy a réinventé le langage et le temps musical en s’inspirant librement de la Nature et des musiques d’Extrême-Orient. C’est dans la continuité de cette démarche que Joanna Goodale propose des créations mêlant le piano aux gongs et bols chantants, selon une trajectoire narrative au fil de l’eau. Debussy in Resonance est une invitation à ressentir la Nature à travers l’univers de Debussy et les sonorités d’Asie, plongeant l’auditeur dans un éveil des sens, où la musique, l’imaginaire et les éléments ne font qu’un. Programme of the concert on 11 May Goodale Opening bols & gongs Debussy Clair de Lune – Suite bergamasque Goodale In the Ocean piano & gongs Debussy La Cathédrale Engloutie – Préludes Reflets dans l’eau – Images I The snow is dancing – Children’s Corner Goodale After the Snow piano & bols & e-bows Debussy Jardins sous la Pluie – Estampes Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut – Images II Goodale In the Temple piano & gongs & bols Debussy Pagodes – Estampes Goodale In Resonance piano & gongs & bols & e-bows Les créations de Joanna Goodale sont inspirées du langage musical de Debussy et des musiques sacrées d’Extrême-Orient avec l’utilisation de bols tibétains, de gongs chinois et d’effets mécaniques sur les cordes du piano (e-bow, patafix, percussion). L’idée de réunir le piano et les percussions d’Asie a été inspirée dans un premier temps par les musiques d’Alain Kremski, pianiste et compositeur. Ces créations se trouvent à la croisée des cultures et des courants musicaux, entre tradition et recherche contemporaine. Ceux sont plus exactement des “comprovisations” où Joanna Goodale improvise à l’intérieur d’une structure plus ou moins définie et selon une narration qui s’insère dans le fil du programme: Opening le silence s’habille de sons – écho d’un rituel In the Ocean chants des baleines – profondeurs – mouvements de surface – écosystèmes fragilisés After the Snow blanc sans fin – pas dans la neige – réveil des oiseaux – rayons de soleil – l’eau solide devient liquide – orage avant la pluie In the Temple souvenir ressuscité – temple vivant – rituel – contemplation In Resonance empreintes – mémoire cellulaire – eaux intérieure

Pre-concert : 6:30 pm – 7 pm

Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-Fonds

Fanfare 3D la fanfare autrement

Together with the Perce-Neige Foundation

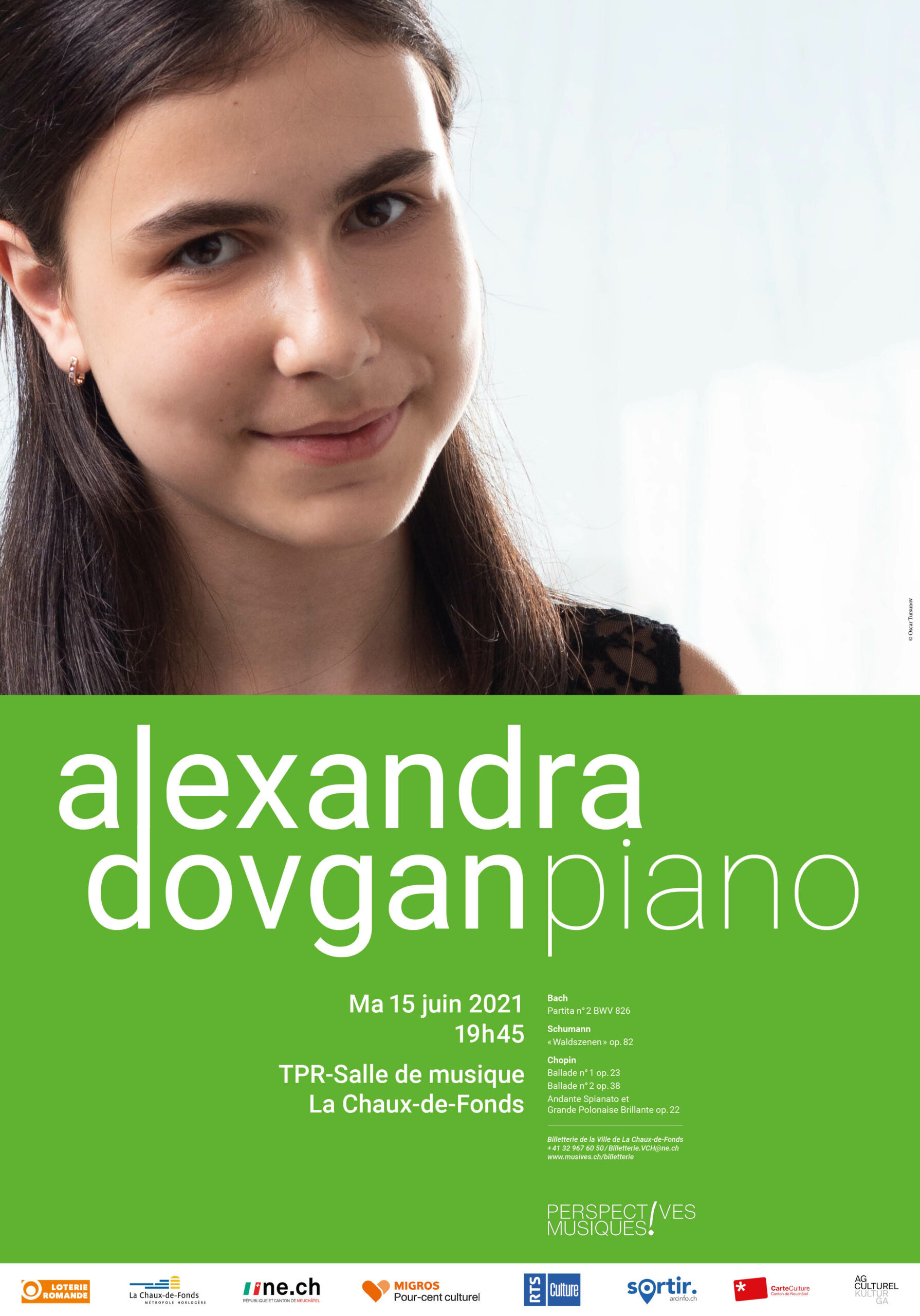

Mardi

15 JUN 2021

7:45 pm – 9:45 pm Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsAlexandra Dovgan, piano

Dans le 1er Concerto pour piano de Mendelssohn

Ticketing

Plan de protection

Rapid test, the easy plan!

Where to get tested in the Canton of Neuchâtel ?

Onedoc.ch

Programme of the concert

Bach

Partita n° 2 en do mineur BWV 826

Schumann

« Waldszenen » op. 82 (Scènes de la Forêt)

Pause

Chopin

Ballade n°1 en sol mineur op. 23

Ballade n°4 en fa mineur op. 52 (remplace la Ballade n°2 en fa majeur op. 38)

Andante Spianato et Grande Polonaise Brillante en mi bémol majeur op. 22

Intergenerational transmission is at the heart of this season’s artistic programming.

After being scheduled for 20 November 2020, then 20 February 2021, the opening concert of the 2020/21 season will finally take place on Tuesday 15 June 2021.

It will be given by the young Russian pianist Alexandra Dovgan, aged 14.

This concert has been chosen by the Canton of Neuchâtel to be one of the three pilot projects to be carried out in June.

The undisputed master of the piano, Grigory Sokolov, speaks very highly of the young musician:

“…This is one of those rare occasions. The twelve-year-old pianist Alexandra Dovgan can hardly be called a wonder child, for while this is a wonder, it is not child’s play. What one hears is a performance by a grown up individual and a Person. It is a special pleasure for me to commend the art of her remarkable music teacher, Mira Marchenko. Yet there are things that cannot be taught and learned. Alexandra Dovgan’s talent is exceptionally harmonious. Her playing is honest and concentrated. I predict a great future for her…”. Grigory Sokolov, 2019

La transmission entre les générations atteint cette saison le cœur de la programmation artistique. Ainsi le concert d’ouverture, un récital de piano, sera donné par la jeune pianiste Alexandra Dovgan, 13 ans, dont le maître incontesté du piano, Grigory Sokolov dit tout le bien qu’il pense, soulignant qu’il ne s’agit en aucun cas d’un enfant prodige mais d’une artiste ayant déjà atteint un niveau incroyable d’accomplissement :

«…C’est l’une de ces rares occasions. La pianiste de douze ans Alexandra Dovgan peut difficilement être qualifiée d’enfant prodige, car s’il est une merveille, son jeu n’est pas celui d’une enfant. C’est un plaisir particulier pour moi de saluer l’art de sa remarquable professeur de musique, Mira Marchenko. Pourtant, il y a des choses qui ne peuvent être enseignées ni apprises. Le talent d’Alexandra Dovgan est exceptionnellement harmonieux. Son jeu est honnête et concentré. Je lui prédis un grand avenir…» Grigory Sokolo

Tuesday

3 MAI 2022

19 h 45 – 21 h 45 Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsMario Brunello violoncelle piccolo

A “piccolo” reading of the Sonatas and Partitas of Johann Sebastian Bach, to be experienced as a new sound experiment, as a journey to the confines of the imagination.

J.-S. Bach

Sonata No. 1 in G minor for violin BWV 1001

J.-S. Bach

Partita No. 1 in B minor for violin BWV 1002

Break

J.-S. Bach

Partita No. 2 in D minor for violin BWV 1004

“Bach was considered an incomparable master in the art of using and manipulating the traditional instruments of his time. His imaginative, even staggering orchestrations bear witness to this. Moreover, the solo parts of his compositions prove his exceptional knowledge of organology, whether wind, rubbed or plucked stringed instruments, or even keyboard instruments. His contemporaries knew Bach above all as a world-famous organist and harpsichord virtuoso”; his second son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, however, testifies that his father had also “perfectly understood the possibilities of all the instruments of the violin family” and cites in support the Solos for violin and cello without bass. Bach certainly studied the playing techniques of the different types of instruments during his early years. Later he certainly benefited from many suggestions from the expert musicians of the Royal Chapels of Weimar and Köthen, who must have inspired him to use the languages of each instrument to invent new timbres and means of expression.

Bach considerably deepened his interest in new sonorities and the development of instrument-specific idioms during his early years in Leipzig (from 1723). In the cantatas of the early years (1723/24), he first experimented with the soft sounds of the oboe d’amore and the hunting oboe. In the second year (1724/25), also known as the “year of the choral cantatas”, it was the turn of the transverse flute, which Bach had hitherto only used for subordinate roles, to be entrusted with extremely virtuosic parts and thus to be given a real boost. The sharp sound of the piccolo recorder is also a novelty in this second cycle.

It is also in this second year that we find the term “cello piccolo” in the airs with demanding solo parts: it seems that Bach only used this instrument in the continuo in his late period. It is possible that he meant to indicate different types of instruments by this term, since the notation of the different voices shows considerable variation, whether in the choice of keys (G, C, tenor or F) or in the order of the voices in the score: sometimes the part is notated in the line of the first violin, so it seems to have been played by a violinist; more often than not, however, the cello piccolo has its own part. It is also striking that from time to time the material for a cantata is presented for this instrument in two voices, in two different keys, at the same time. In these cases, Bach seems to have switched between two types of instruments during the performances, or else he chose, depending on the musician present, another key for the solo part (a violinist would hardly read the key of C or F, for a cellist the key of G was unusual). This confusing observation about the performance material of the cantatas is still a source of discussion today. In addition, there are documents from the second half of the 18th century in which Bach is described as the inventor of the “Viola pomposa“, a large viola tuned like a cello with the addition of an E string. However, the term Viola pomposa does not appear anywhere in Bach’s original sources. It does, however, appear in various chamber music works and concertos by masters of the Berlin school, who could hardly have been aware of an instrument developed in Leipzig. Therefore the viola pomposa must have been a particular form of viola, certainly rare but nevertheless widely used, an instrument therefore played on the shoulder. According to the sources, the parts noted Violine I most likely to be related to the viola pomposa are those of the Cantatas Bleib bei uns, denn es wird Abend werden BWV 6 and Jesu, nun sei gepreiset BWV 41.

The cello piccolo parts, mostly notated in the key of F, of the cantata Also hat Gott die Welt geliebet BWV 68 and the Mass in A Major BWV 234 seem clearly intended for a cello piccolo (C-G-D-A-E chord). And the solo parts too, written on separate sheets, are more convincing from a technical and sonorous point of view on a leg-held instrument.

A further observation about the type of instrument concerns its use in interaction with other instruments. The compositions for viola pomposa by Johann Gottlieb Janitsch, Johann Gottlieb Graun and Georg Philipp Telemann use it exclusively in ensemble music. Bach, on the other hand, uses the cello piccolo in his cantatas preferably as a solo instrument: he hardly plays more than two arias with a high register wind instrument.

The coexistence of two types of instrument with the same tuning is also based on organological research. According to information from Johann Adam Hiller, the Leipzig violin maker Johann Christian Hoffmann built several five-stringed grand violas around 1724 on Bach’s instructions. The inventory of the Köthen Castle Music Chamber also includes an instrument built in 1731 by Hoffmann called “Cello Piculo violin with five strings“. Bach must have been familiar with the five-string cello and its handling already in Köthen’s time, since his six Suites for Solo Cello without Bass, which follow, in a copy by Anna Magdalena Bach, as “Pars 2”, the six Violin Solos dated 1720, seem to include the whole series of instruments known in the 18th century as “Violoncello”, including the five-string cello piccolo. The Sixth Suite in D major is marked “A cinq cordes”. The small size of the instrument as well as the high fifth string make it possible to play similar to the Violin Solos in many respects. Like the Prelude, which works generously with the effects of bariolage, which means that a note is played quickly on an empty string and replayed on the nearest lower string. This technique is very common on the violin and is particularly difficult on the cello. Bach uses it in a limited way at the climax of the Prelude to the First Suite. In the Sixth Suite BWV 1007, on the other hand, the colour scheme becomes the basic thematic idea, and in this sense it has similarities with the Prelude to the Third Partita in E major BWV 1006 for solo violin. The Allemande of the Sixth Suite also recalls, with its broad melodic lines and three- and four-part chords, similar models from the Violin Solos. The most striking passage, however, concerning the violinist’s approach, is found in the Sarabande in the numerous chords, in the polyphony as well as in the barely sketched conduct of the voices.

With his works for solo instrument, Bach dares a means of sound that very few composers before him had explored and whose potential in his time had barely been grasped. While the attempt to present an entire harmonic complex in a single, often interrupted melodic line is at best only partially convincing in pre-existing works, it would seem that it was precisely the challenge presented by this solo instrument that inspired Bach to seek to imitate and even surpass the sonic richness of his great works for keyboard and organ-perhaps also because these could only be sketched by the performer and heard and understood by the imagination of an attentive listener. Philippe Spitta’s words about the Ciaccona of the Second Partita for solo violin, “triumph of spirit over matter”, perfectly define the two monumental soloist cycles for violin and cello. A remark by Johann Friedrich Reichardt goes in the same direction, who recognizes in the mastery demonstrated in the Solos the composer’s ability to move with great freedom and safety within the limits he has imposed on himself.

Bach’s pupil, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, emphasizes above all the capacity for compositional technique demonstrated in these works. According to him, the high school of polyphonic construction lies in the art of avoiding the superfluous: only those who are able to represent the complex secrets of harmony and counterpoint in a work with few voices – that is, transparent – really master it. On the first page of his book Die Kunst des reines Satzes in der Musik (The Art of Pure Composition in Music) published in 1771, Kirnberger, after explaining the two- and three-voice fugues, tells us about works for an unaccompanied melodic instrument: “It is even more difficult to write a simple song without accompaniment, in such a harmonious way that it is not possible to insert another voice without fault, not to mention that the added voice would be quite impossible to sing and clumsy. In this genre, we have from J.S. Bach, without any accompaniment, 6 Sonatas for violin and 6 for cello “. The quite exceptional requirement that Bach faced in knowingly choosing this reduction of sound means consisted in realizing with a melodic instrument having very few possibilities of playing chords and without compromise all the richness of all his harmonic and polyphonic musical language. This approach to the art of composition propels solo works – strangely enough despite their sometimes extremely sharp playing technique – so to speak into the sphere of abstract music, which can be realised in an extremely variable way.

Peter Wollny, Leipzig, août 2019

_______________________________

Peter Wollny is Director of the Bach-Archiv Leipzig and Professor of Musicology at the Leipzig University and at the University der Künste in Berlin. He has also taught at the Humboldt-Universität Berlin, the Technische Universität Dresden and the Musikhochschule Weimar. He has published several volumes of the Neue Bach-Ausgabe, is editor-in-chief of “C.P.E Bach: The Complete Works” and editor of the Bach-Jahrbuch. He has published numerous writings on the Bach family and on the history of music from the 17th to the 19th century. His monograph on the stylistic changes in Protestant church music after the Thirty Years’ War was published in 2017.

BACH AND THE CELLO PICCOLO

Mario Brunello, 1st Prize at the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1986, makes us rediscover the cello piccolo. Smaller than the cello, the cello piccolo, a five-stringed instrument (C-G-D-A-E chord), also stands between the legs. The Leipzig violin maker Johann Christian Hoffmann is said to have built several 5-string grand violas around 1724, following Bach’s instructions. There is also a trace of an instrument built in 1731 by Hoffmann called “Cello Piculo violin with 5 strings”. Bach must have been familiar with this instrument whose small size and high 5th string allow a playing that is close to the violin solos in many respects, while offering a full and generous sound.

Wednesday

1 JUN 2022

7:45 pm – 9:15 pm Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsJean Rondeau clavecin Thomas Dunford luth

Dialogue on the rising and King’s bedtime

The reign of Louis XIV (from 1661 to 1715) was particularly rich artistically. A great lover of art in general, and music in particular, the king sang, played the guitar and had a strong taste for dancing. Music was omnipresent at court and accompanied both exceptional moments and daily rituals. From the Great Rising to Supper and Bedtime, the rigorous ceremonial that punctuated the monarch’s life gave rise to pieces by major players in the musical life of Louis XIV’s long reign.

Robert De Visée (circa 1650-1665 – after 1732) Suite in D minor (lute and harpsichord) Marin Marais (1656-1728) Les Voix humaines, Lentement (from the Suite No. 3, Second book of viola da gamba and luth) François Couperin (1668-1733) Premier Prélude en do majeur (from L’Art de toucher le clavecin) La Ménetou, Le Dodo ou l’amour au berceau, La Ténébreuse, La Favorite (lute and harpsichord) Jean-Henry D’Anglebert (1629-1691) Prélude (from the Suite in D minor, harpsichord) Sarabande Grave (lute and harpsichord) Antoine Forqueray (father, 1672-1745) Jean-Baptiste Antoine Forqueray (son, 1699-1745) La Portugaise La Sylva Jupiter (Lute and harpsichord) At the beginning of the Baroque period, French composers of solo instrumental music created a language that would inspire many composers from the rest of Europe. In the 17th century, the lute found its home in France: while the first books of lute pieces contain primarily transcriptions of vocal works, later collections offer a totally instrumental repertoire. Virtuoso lutenists such as Denis Gaultier considerably developed the language of the lute: free polyphonic writing, complex ornaments and a broken style (the arpeggio).

Little by little, the guitar came to the forefront of the scene (witness the paintings of Watteau, where courtiers and shepherds prefer the guitar to the lute). One musician was to arouse the court’s infatuation with this instrument, certainly less noble, but nevertheless simpler technically speaking: it was Robert de Visée, composer, multi-instrumentalist and guitar teacher to the king. Often required to instruct or sometimes entertain Monseigneur le Dauphin (the future Louis XV), Robert de Visée also stood at the monarch’s bedside in the evening to play the guitar. The work we will hear here is the Suite in D minor: it is a suite of dances in which the contrasts between each of the movements are explored with a unifying principle, the single key. At this time, dance dominated French music. Pour le musicien, la connoissance de l’art de la danse est d’un grand secours pour mieux connoître le vray mouvement de chaque pièce et conserver le mouvement de la mesure. Robert de Visée often took part in Mme de Maintenon’s sumptuous soirées, where his partners included Couperin, Rebel and Forqueray.

Antoine Forqueray, an outstanding gambist, has composed numerous pieces for the viol. Considering himself to be the only one capable of interpreting them, he opposed their publication all his life. It was his son, Jean-Baptiste, also an excellent gambist, who published his father’s works for viola da gamba as well as these same pieces transcribed for the harpsichord (where he set about preserving the low tessitura proper to the viol). At that time, most of the works were works in movement: when a composer wrote a piece, he or other musicians transposed it and adapted it to different types of instrumentation. It is on the harpsichord that La Portugaise, La Sylva, La Jupiter will be performed: pieces characterized by great theatricality and formidable sound power.

It can be stated that no one has surpassed Marais, only one man has equalled him, the famous Forqueray. By saying that one played like a god and the other like a devil, the monarch himself seems to have had fun orchestrating the rivalry between Marais and Forqueray. Marin Marais, an extremely talented and prolific composer and performer, brought the art of the viol to a very high level of perfection. Between 1686 and 1725, he published five volumes of viol pieces, from which Les Voix Humaines, a work of great sensuality, is extracted. As most composers of his time, Marais drew his inspiration from literary sources, more precisely theatrical sources (Molière and Racine) and was inspired by the language of lyrical tragedy, of which Jean-Baptiste Lully is the most illustrious representative (the inescapable Monsieur de Lully, who appears on most of the dedications of the works heard tonight).

Gaultier’s musical legacy survives in harpsichord music. It is in Jacques Champion de Chambonnières that the French harpsichord school finds its first great representative: a harpsichordist at the French court, his influence is considerable, especially on Louis Couperin (François’ uncle) and Jean-Henri d’Anglebert (who took over as Ordinary of the Music of the King’s Chamber for the harpsichord). In 1689, the latter published his Pièces de clavecin, the only work in which he added transcriptions of works by Lully to the dance suites of his composition. In France, this book is the first printed work to include a table of ornaments indicating the manner in which they are to be performed. We will discover the Prelude in D minor and the Sarabande Grave.

Nicknamed “le Grand” because of his exceptional mastery of the organ and undisputed master of the harpsichord, François Couperin succeeded Jean-Henri d’Anglebert as court organist and also held the position of organist at the Chapelle Royale. Known today notably for his moving Leçons de ténèbres, he published a reference treatise, L’art de toucher le clavecin, which instructs the performer on the beautiful Touch of the Harpsichord and the taste appropriate to this instrument. His mutinous, sensual pieces, with poetic and mischievous titles, are as many small portraits and landscapes, bringing Couperin closer to the fabulist La Fontaine or the painter Watteau.

During this royal evening, Jean Rondeau and Thomas Dunford, two alchemists who are keen on experimentation, will revisit the subtle and sublime French baroque of this period rich in contrasts, where the music is at once refined, flamboyant, theatrical and poetic. The King is dead! Long live the music!

Comment: Céline Hänni, Centre de culture ABC

At the beginning of the Baroque period, French composers of solo instrumental music created a language that would inspire many composers from the rest of Europe. In the 17th century, the lute found its home in France: while the first books of lute pieces contain primarily transcriptions of vocal works, later collections offer a totally instrumental repertoire. Virtuoso lutenists such as Denis Gaultier considerably developed the language of the lute: free polyphonic writing, complex ornaments and a broken style (the arpeggio).

Little by little, the guitar came to the forefront of the scene (witness the paintings of Watteau, where courtiers and shepherds prefer the guitar to the lute). One musician was to arouse the court’s infatuation with this instrument, certainly less noble, but nevertheless simpler technically speaking: it was Robert de Visée, composer, multi-instrumentalist and guitar teacher to the king. Often required to instruct or sometimes entertain Monseigneur le Dauphin (the future Louis XV), Robert de Visée also stood at the monarch’s bedside in the evening to play the guitar. The work we will hear here is the Suite in D minor: it is a suite of dances in which the contrasts between each of the movements are explored with a unifying principle, the single key. At this time, dance dominated French music. Pour le musicien, la connoissance de l’art de la danse est d’un grand secours pour mieux connoître le vray mouvement de chaque pièce et conserver le mouvement de la mesure. Robert de Visée often took part in Mme de Maintenon’s sumptuous soirées, where his partners included Couperin, Rebel and Forqueray.

Antoine Forqueray, an outstanding gambist, has composed numerous pieces for the viol. Considering himself to be the only one capable of interpreting them, he opposed their publication all his life. It was his son, Jean-Baptiste, also an excellent gambist, who published his father’s works for viola da gamba as well as these same pieces transcribed for the harpsichord (where he set about preserving the low tessitura proper to the viol). At that time, most of the works were works in movement: when a composer wrote a piece, he or other musicians transposed it and adapted it to different types of instrumentation. It is on the harpsichord that La Portugaise, La Sylva, La Jupiter will be performed: pieces characterized by great theatricality and formidable sound power.

It can be stated that no one has surpassed Marais, only one man has equalled him, the famous Forqueray. By saying that one played like a god and the other like a devil, the monarch himself seems to have had fun orchestrating the rivalry between Marais and Forqueray. Marin Marais, an extremely talented and prolific composer and performer, brought the art of the viol to a very high level of perfection. Between 1686 and 1725, he published five volumes of viol pieces, from which Les Voix Humaines, a work of great sensuality, is extracted. As most composers of his time, Marais drew his inspiration from literary sources, more precisely theatrical sources (Molière and Racine) and was inspired by the language of lyrical tragedy, of which Jean-Baptiste Lully is the most illustrious representative (the inescapable Monsieur de Lully, who appears on most of the dedications of the works heard tonight).

Gaultier’s musical legacy survives in harpsichord music. It is in Jacques Champion de Chambonnières that the French harpsichord school finds its first great representative: a harpsichordist at the French court, his influence is considerable, especially on Louis Couperin (François’ uncle) and Jean-Henri d’Anglebert (who took over as Ordinary of the Music of the King’s Chamber for the harpsichord). In 1689, the latter published his Pièces de clavecin, the only work in which he added transcriptions of works by Lully to the dance suites of his composition. In France, this book is the first printed work to include a table of ornaments indicating the manner in which they are to be performed. We will discover the Prelude in D minor and the Sarabande Grave.

Nicknamed “le Grand” because of his exceptional mastery of the organ and undisputed master of the harpsichord, François Couperin succeeded Jean-Henri d’Anglebert as court organist and also held the position of organist at the Chapelle Royale. Known today notably for his moving Leçons de ténèbres, he published a reference treatise, L’art de toucher le clavecin, which instructs the performer on the beautiful Touch of the Harpsichord and the taste appropriate to this instrument. His mutinous, sensual pieces, with poetic and mischievous titles, are as many small portraits and landscapes, bringing Couperin closer to the fabulist La Fontaine or the painter Watteau.

During this royal evening, Jean Rondeau and Thomas Dunford, two alchemists who are keen on experimentation, will revisit the subtle and sublime French baroque of this period rich in contrasts, where the music is at once refined, flamboyant, theatrical and poetic. The King is dead! Long live the music!

Comment: Céline Hänni, Centre de culture ABC

Thursday

23 JUN 2022

7:45 pm – 9:45 pm Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsJupiter Ensemble

Thomas Dunford direction et luth

Lea Desandre mezzo-soprano

AMAZONS

For her first solo recital on disc, rising star Lea Desandre faithfully surrounds herself with the musicians of Jupiter, with whom she has collaborated since the Ensemble’s inception. The Amazons will be featured in a Franco-Italian program, the artist’s nationalities, crossing the baroque repertoire with numerous world rediscoveries.The figures of the Amazons were a great source of inspiration for 18th century composers. We then find in their works recurring female characters: queens (Antiope, Mitilene, Hippolyte, Talestri, Marthésie) or androgynous figures, both feminine and warlike. From the victorious laurels of war to the passions and amorous complaints, this programme is a dedication to these feminine and emblematic figures, and a journey into the state of mind and the state of being of these women warriors. This diversity of characters makes it possible to alternate very contrasting arias: lamenti, great lyrical scenes, war plays, tales of fury, recitatives, tender tunes, instrumental pieces.

Francesco PROVENZALE Lo schiavo di sua moglie « Non posso far » (1’30) « Lascatemi morire » (3’) Giovanni Buonaventura VIVIANI Mitilene « Muove il pie fuorie d’averno » (1’15) Francesco CAVALLI Ercole Amante Sinfonia Acte 1 (1’) Francesco PROVENZALE Lo schiavo di sua moglie « Quanto siete per me » (2’) Giovanni Buonaventura VIVIANI Mitilene « Congiuro tutto l’inferno » (2’) Tarquinio MERULA Chaconne (4’) Giovanni Buonaventura VIVIANI Mitilene « Preparate la tomba » (3’) Carlo PALLAVICINO L’Antiope « Mio cor, io non la so comprendere » (2’15) Georg Caspar SCHÜRMANN Die Getreue Alceste Sinfonia pour la tempête (1’) Carlo PALLAVICINO L’Antiope : « Vieni, corri » (2’20) , « Sdegni furori barbari » (1’30) François-André Danican PHILIDOR Les Amazones Marche – Thalestris – Marche (2’30) André-Cardinal DESTOUCHES Marthésie « Faible fierté, gloire impuissante » (3’15) François COUPERIN Second livre des pièces de clavecin Dixième ordre : L’Amazone (1’30) André-Cardinal DESTOUCHES Marthésie « Reignez obscure nuit » (3’17) Marin MARAIS Badinage (4’) André-Cardinal DESTOUCHES Marthésie ( « Ô Mort ! Ô triste mort » (2’13) François COUPERIN Second livre des pièces de clavecin Sixième ordre Les Barricades mystérieuses (arrangement pour luth) (2’30) André-Cardinal DESTOUCHES Marthésie « Quels coups me réservait la colère céleste » (4’30) Antonio VIVALDI Ercole sul Termodonte 1er mouvement, Ouverture (1’40) Giuseppe DE BOTTIS Mitilene Regina delle Amazzoni (1707) , « Che farai misero core » (4’) Georg Caspar SCHÜRMANN Die Getreue Alceste (1719) « Non ha fortuna il pianto moi » (3’15) Antonio VIVALDI Ercole sul Termodonte (1723) 2ème mouvement, Ouverture (2’) Giuseppe DE BOTTIS Mitilene Regina delle Amazzoni (1707) « Lieti fiori » (3’15), « Sdegno all’armi alle vendette » (2’) Antonio VIVALDI Ercole sul Termodonte (1723) 3ème mouvement, Ouverture (0’50) « Onde chiare che sussurate » (5’30), « Scendero, volero, gridero » (1’30)

Friday

31 MAR 2023

7:45 pm – 9:45 pm Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsSignum saxophone quartet

Alexej Gerassimez multi-percussionist

STARRY NIGHT

Five young musicians create soundscapes that no one has ever explored before as they embark on a Star Trek-like journey.

Percussionist Alexej Gerassimez and the SIGNUM saxophone quartet are all highly acclaimed performers and universalists of the young classical music scene. These are five virtuosos who love to break down barriers between concert and performance, between styles and genres and between composition and improvisation. Crossing borders is also the central focus of the programme which the multi-percussionist and four saxophonists have conceived together. Familiar classics such as Holst’s “Planets” are followed by contemporary works by Alexej Gerassimez (“Rebirth”) and Steve Martland (“Starry Night”) and by a new piece specially commissioned from the New Zealand composer John Psathas. Cosmic sound tracks by John Williams rub shoulders with fire crackers from the world of rock music (AC/DC). The theatrically choreographed work “Bad Touch“ and a series of moderations define the concert cosmos.In putting together their set list, the musicians have sought inspiration from the major questions facing mankind. Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? Their music takes the audience on a trip deep into space and right into the heart of our subconscious, where we confront our fears, dreams and yearnings.

In short, the concert becomes a spatial experience which appeals to all ages and all types of audience – exciting and soothing, surprising and familiar, romantic and rocking, grounded and other worldly.

Alexej Gerassimez (1987) Rebirth for percussion and saxophone quartet Gustav Holst (1874-1934) The Planets Transcription for percussion and saxophone quartet, by Hugo Van Rechem Uranus Venus Jupiter Casey Cangelosi Bad Touch John Williams (1932) Flying Theme (E.T.) Arrangement for saxophone quartet and percussion by Alexej Gerassimez Break Alexej Gerassimez (1987) Asventuras for Snare Drum Solo Steve Martland (1954-2013) Starry Night Transcription for percussion and saxophone quartet AC/DC (Angus Young, Malcolm Young) Thunderstruck Transcription for percussion and saxophone quartet by SIGNUM saxophone quartet John Psathas (1966) Connectome (2019) Commission piece for Alexej Gerassimez and SIGNUM saxophone quartet Pashupatastra Farewell to Flesh Rom in Space

Friday

2 JUN 2023

7:45 pm – 10 pm Salle de musique / avenue Léopold-Robert 27, La Chaux-de-FondsGrigory Sokolov piano

Previous concerts

Photographic credits:

Alexandra Dovgan © Oscar Tursunov

Jupiter Ensemble website, screenshot from the video of the Vivaldi CD recording

Lea Desandre © C. Ledroit Perrin

Signum © Andrej Grilc

Alexej Gerassimez © Nikolaj Lund

Grigory Sokolov © Vico Chamla

Sources:

Text “Bach and the violoncello piccolo” (pages 4 to 6) :

CD Sonatas & Partitas for solo violoncello piccolo

Johann Sebastian Bach

Label ARCANA / Bach Brunello Series